News — Julia Stepanuk, Ph.D., Quantitative Ecologist

Julia is no stranger to the ocean. At only 14 years old, she volunteered for Allied Whale and the Bar Harbor Whale Watch Company. Rising through the ranks of the Company over the years, she began guiding whale watching trips and collecting data from the boat as a scientist.

Leading up to graduate school, Julia spent months at sea learning the ropes (literally) of operating a 134-foot Tall Ship operated by Sea Education Association, sailing from Hawaii to Tahiti and San Diego to Nuku Hiva of the Marquesas Islands.

During her voyages, Julia collected and analyzed data that would contribute to long-standing oceanographic datasets collected by the organization. These trips through the Pacific Ocean and along the coasts of Maine, New York, and Antarctica taught her the leadership and teamwork skills she would use throughout her career.

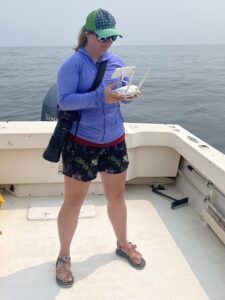

Julia’s talents are not limited to the ocean, however. To be an excellent scientist, you have to not only become an expert in your chosen field, but you must also master complementary skills that help you stand out from the crowd. Luckily for Julia, mathematics and coding come naturally. She can transform spreadsheets of data into models that can answer complex questions about whale populations that are meaningful to wildlife managers from state and federal organizations. One of Julia’s methods of data collection involves using drone imagery. Working out of Long Island, New York, Julia has spent many hours operating a drone from a boat, learning how to position it over a humpback whale to get the perfect shot, tip to tail.

Using this method, she has collected images of 75 individuals over 5 years. These images were used to determine the health of the humpback whale population in the New York Bight region. Health was evaluated by using body size characteristics—sort of like a body mass index (BMI) for people. “Their size reflects how important whales are to the ecosystems in which they live,” Julia explains. She was even able to forecast whales like the weather, using models that can predict when and how many humpback whales will be off the coast of Long Island. This is important because whales often come in close contact with fishing vessels and recreational watercraft, near and far from shore. Knowing how many whales are out there and when helps to prevent collisions, saving lives and preventing serious injury.

Through her research, Julia has measured humpback whales whose sizes ranged from 30 to 50 feet in length. After all her years of studying these gentle giants, it’s still not lost on Julia just how impressive their size is. When asked what she wishes people understood about whales, she responded simply, “It’s just so cool how big they are!” Her answer was gleeful. Surely imagining the many close encounters she has experienced throughout her career, it’s that kind of enthusiasm that fuels the dedication to her work at BRI.

What excites Julia most about the Marine Mammal Program is that she can focus on preventing negative impacts to whales before they have a chance to happen. Noise pollution from vessel traffic, vessel strikes, and fishing gear entanglement are some of the many threats Julia hopes to address. To add to her challenges, the effects of climate change present a slew of unexpected problems that could amplify existing threats. Locally and globally, there is a wealth of information about marine mammals, but there is still so much to learn about their presence in the Gulf of Maine. Through field surveys, statistical modeling, and collaboration with other agencies, universities, and conservation groups, Julia is on a quest to make those discoveries.

Megan Ferguson, Ph.D., Quantitative Ecologist

Hailing from Salt Lake City, Utah, Megan didn’t grow up in an environment that would naturally foster an interest in marine biology. Luckily for BRI, Megan spent her summers on the California coast where she fell in love with the ocean. Watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries with her family also ignited her burgeoning passion.

When it came time to think about college, it was no surprise that she chose the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences in Seattle. Her first formative experience was during her internship with the Marine Mammal Laboratory at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, where she was immersed in work at the intersection of applied ecology, mathematics, and wildlife management. This interdisciplinary field of studying marine mammals was where Megan felt most inspired. From there, Megan’s career led her to the prestigious Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, where she studied biological oceanography.

A natural problem solver, Megan wanted to answer the question: How do all of the pieces (biology, physical oceanography, geography, human activities) interact to shape and transform ecosystems?

To find out, she spent weeks on research vessels in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean performing visual and acoustic sampling of whales and dolphins, and collecting physical and biological oceanographic samples. Her most profound experience though, came in an entirely different environment: the Alaskan Arctic.

From the vantage point of an airplane, Megan set out to estimate sizes of whale populations vital to Indigenous peoples in Alaska. Through collaboration with Native subsistence hunters, scientists, and wildlife managers, she worked with the Alaska Beluga Whale Committee and Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission to conserve and manage belugas and bowhead whales using a combination of Indigenous knowledge and western science. On a larger scale, she developed methods to delineate marine areas that are important to cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) for feeding, migration, and reproduction.

The Pacific Arctic is in transition. Common cetacean species in this region are bowhead, beluga, and gray whales. However, during Megan’s time collecting data in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, she noticed an uptick in sub-Arctic species including fin, minke, and humpback whales. Like many species on land, some marine mammals are shifting their ranges north due to climate change. In addition, with fewer days of ice obstructing the Bering Strait (also called the Northwest Passage), there is a longer season during which vessel traffic can pass between the Chukchi and Bering seas. With more vessels comes more noise, which is disruptive to whale communication and increases the risk of collision and accidental release of pollutants and debris.

Megan is always looking for solutions to complex ecological issues. Through the Marine Mammal Program, she looks forward to continuing her work collaborating with Indigenous communities; local, state, and federal organizations; nonprofits; developers; universities; and fishermen. Working alongside Julia, these pioneering scientists intend to use the best available information in the best way possible to achieve conservation and management goals for marine mammals. Their combined backgrounds will enable them to tackle many of the present and future challenges to marine mammals.

More stories on .

MEDIA CONTACT

Register for reporter access to contact detailsArticle Multimedia

Credit:

Caption: Julia controls a drone flying over open ocean. Once she spots a whale, she sends the drone 100-120 feet high and aims for the perfect shot. All work was conducted in compliance with federal research permits

Credit:

Caption: Megan prepares to board a twin-engine Turbo Commander in Utqiaġvik (pronounced oot-kay-ahg-vik), Alaska to conduct surveys. If conditions are optimal, her crew can make two survey flights in a 12-14 hour day, which includes time flying, refueling, data collection, and a survey report.