News — Mercury studies in Indonesia. Climate change studies in Tanzania. Biodiversity studies in South Dakota. Marine mammal surveys in the Atlantic Ocean. BRI’s conservation biologists are literally all over the map. Over the course of 25 years, a small group of wildlife researchers monitoring mercury in loons and eagles in Maine grew into a global organization that works at the highest levels of international environmental research. With that advantage comes the responsibility of informing and helping shape the contours of policy—a responsibility BRI founder and chief scientist David Evers takes very seriously.

BRI is an organization of scientists whose research aims to answer questions critical for maintaining a healthy earth: How do ecosystems work? How do contaminants affect those ecosystems? How do wildlife respond to environmental stressors over time? But an additional role that BRI embraces is to provide a service to policymakers. “As a scientist, you want to understand and learn for the sake of learning, for the sake of knowledge,” says Evers. “But the power is in bringing that knowledge to the people who can use it.”

The foundation for this journey began with BRI’s mission, which placed innovative wildlife research and scientific integrity on an equal footing with sharing knowledge gained from this research with those who make policy decisions. Building upon early successes in its research collaborations, BRI has cultivated the expertise and resources needed to develop innovative study designs, achieve more precise analysis, and maintain objective and informative interpretation.

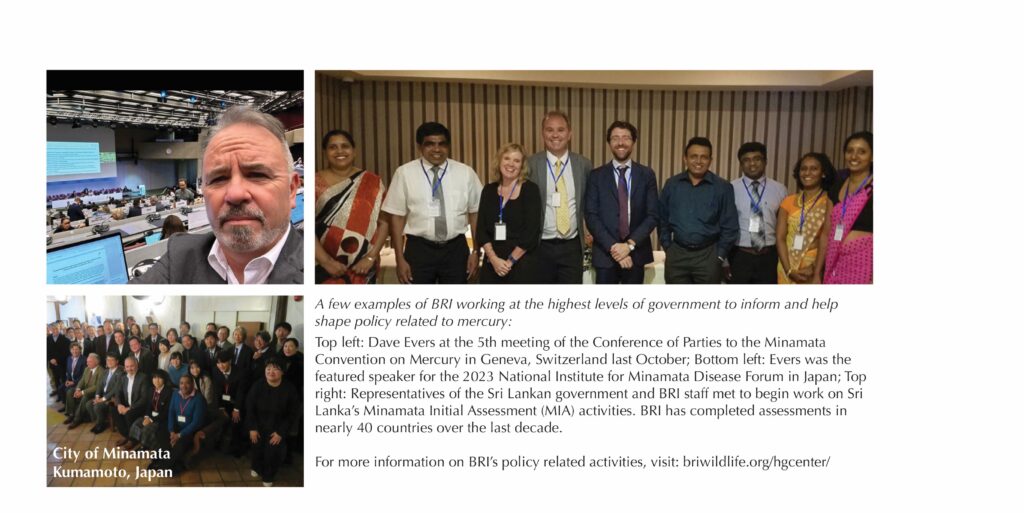

A pivotal moment for BRI came in 2011 when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency invited Evers, renowned in his field of mercury studies, to join the scientific committee for the United Nation’s first global agreement designed to address contamination from a heavy metal—the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Evers understood the importance of providing critical scientific data to the international delegates responsible for crafting this policy, but he saw BRI’s research stretching far beyond the ratification of the treaty.

Tracking Mercury on a Global Scale

The Minamata Convention was put into force in October of 2017. An important provision of the Convention is to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the adopted measures and its implementation—no small feat given the complexities of how mercury moves through air, water, and land.

With years of published mercury data on wildlife in North America compiled into a single database, BRI was poised to take the lead in developing methods for collecting mercury data and monitoring changes over time on a global scale—exactly what the Convention needed. Known as the Global Biotic Mercury Synthesis (GBMS), this database now includes more than 550,000 data points detailing each organism sampled, its sampling location, and its ecological profile. That information is used to understand patterns of mercury concentrations in wildlife across time and space, helpful in identifying species and ecosystems most at risk. Mapping risk helps improve efforts to reduce the impact of mercury pollution on people and the environment.

In addition to the GBMS database, which contains only peer-reviewed published data, the Secretariat of the Minamata Convention has initiated an Open-ended Science Group (OESG) to help monitor mercury reduction in each country that has ratified and is a Party to the Convention. Made up of one representative from each Party, this group will contribute countrywide data, both published and unpublished, pertaining to mercury monitoring in air, water, wildlife, and people. BRI is the lead organizer for this group and is developing protocols to standardize and harmonize data originating from various sources so that the information is presented in a clear and accessible format.

Building on Commitment, Collaboration, and Communication

As BRI has grown, the organization has made it a priority to develop a standard of science communications that provide nonscientists clear information—facts about a specific problem, such as mercury contamination—and how BRI is gathering, analyzing, and interpreting those facts. To further enhance global collaboration and communication, BRI is building a staff of highly skilled scientists who also have experience working in different sectors, including policy and industry.

It’s not an understatement to say that there are huge environmental issues facing our world today. On the horizon, BRI has projects that aim to reduce the triple threat of climate change, loss of biodiversity, and ongoing contamination of our natural resources. “To me, it’s all about building blocks, building off of past successes and platforms that were generated and developed,” says Evers. “And then working to build those blocks up to something higher, working toward more elevated goals.”

The Minamata Convention is one of those building blocks for BRI, which has led us to collaborate with other Conventions including the Convention for Biological Diversity and the Framework Convention on Climate Change. “Our niche is as detectives for the environment. Whether we are working in Maine or in Tanzania, wildlife need a voice. BRI is one such voice.”

More stories on .