News — In the past six months, has spoken to more researchers than she has in her last 14 years at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“The last thing an autistic person wants to hear is, ‘You need to talk to people,’” said Hetrick, a professor and graduate coordinator of art education in the School of Art and Design. “But this idea was more important to me than my own comfort, so I overlooked my fear of talking to strangers.”

Talking to strangers. Knocking on doors. Entering terms like “phenomenology” and “comorbidities” and “genomics” into search bars. All necessary, if not entirely comfortable, strategies for assembling a team to reimagine how autism is studied and who can study it.

As a , Hetrick published three op-eds in and chronicling her late-in-life autism diagnosis and tackling topics like neurodiversity and social masking in academia. Her own research prioritizes understanding and validating the experiences of so-called “autie profs,” she said, using a term of endearment for autistic professors.

“Autistic voices are not heard in the research space,” Hetrick said. “I am hoping to use my autistic lived experience and neurodiverse abilities to close this gap and address the injustice that often happens when researchers do research on autistics, not with autistics.”

At the suggestion of colleague , Hetrick joined the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology last summer. She sought a collaborator to supplement her autistic experience with knowledge of the human genome — specifically, how genes may explain the slew of commonly experienced alongside autism.

“There’s a laundry list of co-occurring conditions that most of us have,” Hetrick said, mentioning . “If we all have these specific things, there has to be something happening at the molecular level, right? It can’t be a coincidence.”

Hetrick wondered if there might be an absence or collection (“or constellation”) of genes underpinning these co-occurring conditions. So, she assembled a research constellation of her own. At the suggestion of Susan Martinis, the vice chancellor of research and innovation at Illinois, Hetrick started with all-star RNA biologist .

A geneticist by training, Ceman is a Beckman affiliate and a professor of cell and developmental biology. She studies the relay race that plays out among our DNA, mRNA and proteins. Since DNA cannot leave the nucleus, the mRNA acts as a messenger (that’s what the M stands for) between the double helix and our body’s proteins, passing the biological baton to relay orders about which proteins to create and what they should do. This function is called protein encoding.

Hetrick was interested in Ceman’s recent study, where she removed one specific gene from a mouse’s DNA. Ceman observed that the mouse in question developed an enhanced fear memory — a sharper recollection for fear-inducing experiences.

Coincidentally (or perhaps constellation-ally), fear memory is known to co-occur with autism.

“I am familiar with the genes implicated in autism from my previous work on Fragile X syndrome and from teaching,” Ceman said. “But I hadn’t appreciated how much of a problem [fear memory] is in the autism community.”

Hetrick stumbled upon her second collaborator, neuroscientist Tracey Wszalek, at a shared lunch table at the Beckman Institute, where Beckman’s was hosting a “Meet the researchers”-style mixer with scholars from Pavilion Foundation School.

“It was a wonderful happenstance,” said Wszalek, who directs Beckman’s and co-directs the . “Laura [Hetrick] told me about this work, and I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting to do imaging as well?’”

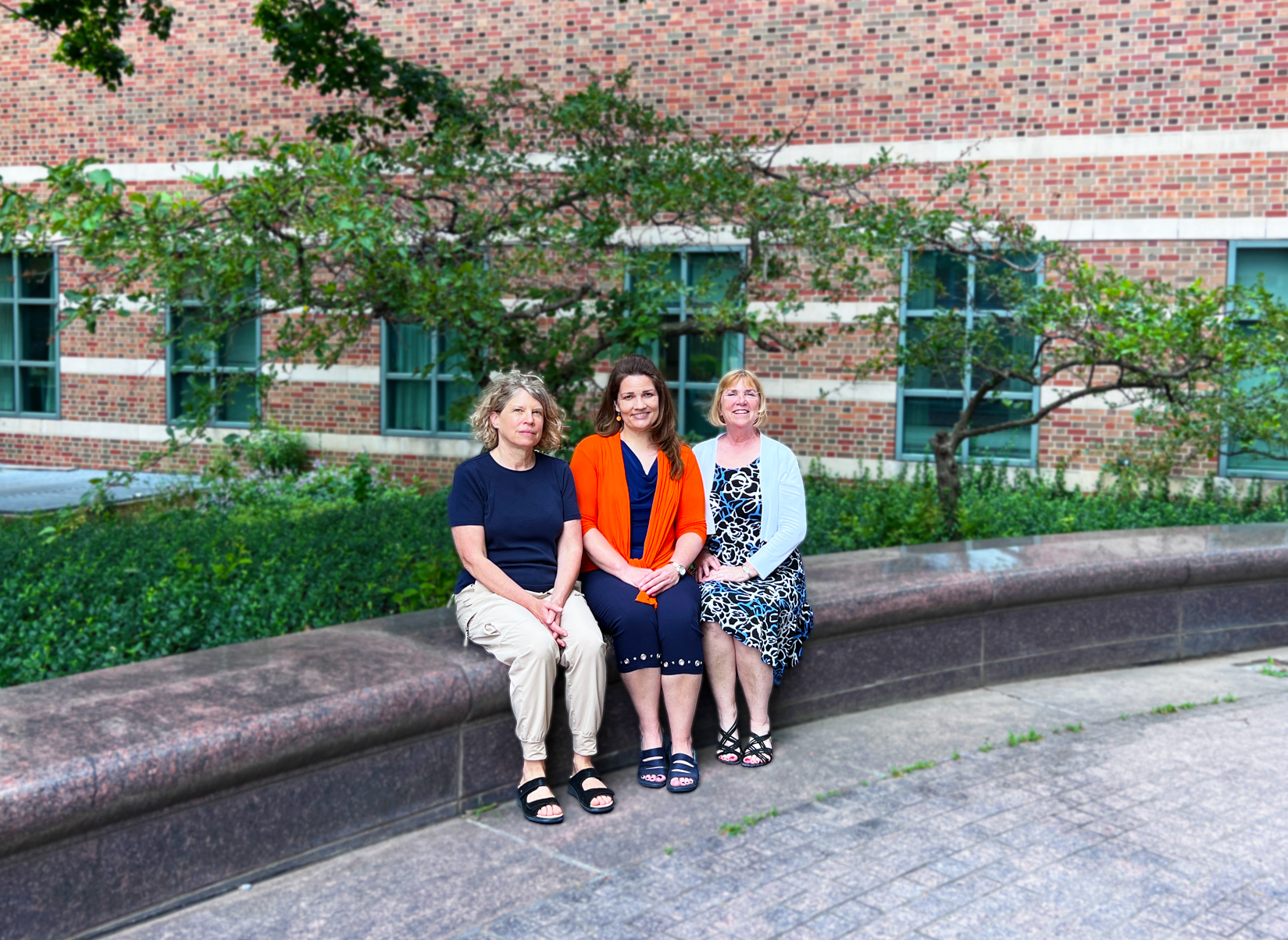

Wszalek, Hetrick and Ceman announced their partnership at a last April where famed researcher and Illinois alumna Temple Grandin commentated.

“It’s really like a mutual admiration society,” Wszalek said, “which I think in life is more necessary than we realize.”

Their first project will combine genetics, neuroimaging and lived experience to holistically describe one autistic individual: Hetrick.

“In other words: Here’s what it feels like, here’s what’s happening inside my brain, and here’s how that is expressed at the molecular level,” she said.

First, the team will sequence Hetrick’s entire genome with state-of-the-art equipment at campus' . Because genetic information is consistent throughout the body, they can do this with a simple blood draw.

Genetic information in hand, the researchers will move to the Carle Illinois Advanced Imaging Center, which houses the only 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging scanner in the state. They’ll use the scanner to map Hetrick’s brain, measure the thickness of grey and white matter, study brain tissue and tune into to how each region communicates with its neighbors — all clues as to which proteins are present and how they behave. The researchers will also note opportunities to improve the MRI experience for autistic participants; for example, making the actual scan time more comfortable and less stimulating.

Finally, the researchers can use Hetrick’s DNA and brain images to make inferences about her RNA (the baton-carrying intermediary), which is impossible to sample noninvasively.

All data, or course, will be received in the context of Hetrick’s lived experience.

Eventually, the researchers hope to compare Hetrick’s data with that of participants in the , or CUPS, a long-term brain imaging study collecting similar information from participants in local communities. The researchers said that Temple Grandin’s genome, which was in 2021, may also provide an important data set for comparison.

For now, the researchers’ priorities are securing funding and homing in on research questions: what Hetrick calls “the folding and unfolding of all the messiness of getting to the actual research.”

Through the folds (interpersonal and brain-wise), the team adopts two key tenets: humility and vulnerability.

“In working together, we can be better than the sum of our parts,” Hetrick said. “I’ve seen collaboration, but I haven’t seen it to this degree …. I have so much respect for these two women.”

The team anticipates results in the next 5 years (“You can quote me on that!” Hetrick said), but they intend to adapt and account for additional perspectives along the way.

“If we can do this for the autistic population, we can do it for other people, too,” Hetrick said. “We’re benefitting a marginalized population first, which I think we should do, but if we can help the rest of humanity in the process, I think that’s fantastic and even more than my initial goal.”

Further reading on fear memory and autism provided by the researchers:

Haruvi-Lamdan, N., D. Horesh and O. Golan (2018). "PTSD and autism spectrum disorder: Co-morbidity, gaps in research, and potential shared mechanisms." Psychol Trauma 10(3): 290-299.

Rumball, F., L. Brook, F. Happé and A. Karl (2021). "Heightened risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with autism spectrum disorder: The role of cumulative trauma and memory deficits." Res Dev Disabil 110: 103848.

Rumball, F., F. Happé and N. Grey (2020). "Experience of Trauma and PTSD Symptoms in Autistic Adults: Risk of PTSD Development Following DSM-5 and Non-DSM-5 Traumatic Life Events." Autism Research 13(12): 2122-2132

MEDIA CONTACT

Register for reporter access to contact detailsRELATED EXPERTS

Laura Hetrick

Associate professor of art education

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign